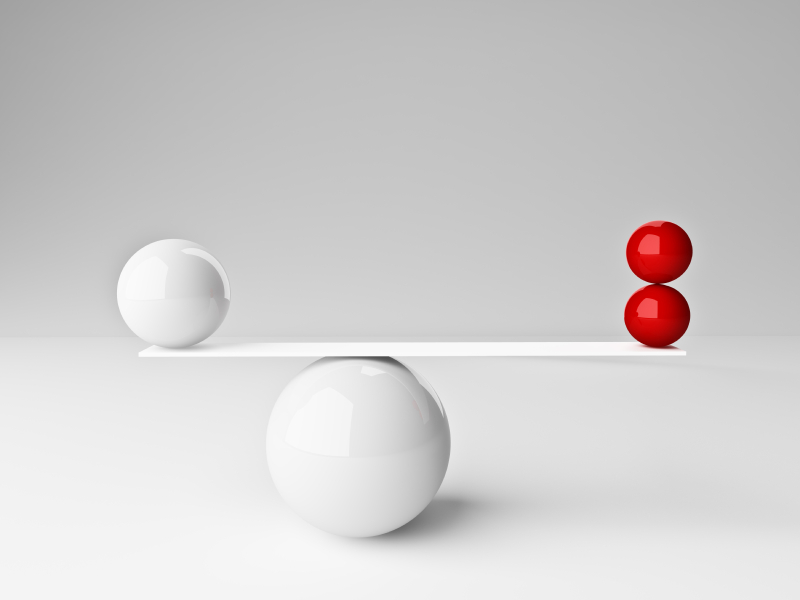

IF ALL POVERTY IS RELATIVE – HOW MUCH IS ‘ENOUGH’? We advocate the 7 Layer Poverty Model, where extreme poverty is simply understood to imply: ‘not enough of the 7 humanitarian basics’. Other posts & pages on this site cover what those basics are and how the model uses them. Since poverty is fundamentally understood to be a relative concept, one person can be poorer than another (using some agreed measure), yet it need not be considered a problem. Here we encounter the idea of Variance versus Significance with reference to relative poverty.

VARIANCE VERSUS SIGNIFICANCE Two people both need drinking water. Let’s say we’ve assessed that they both need 3 litres per day to thrive, within a given environment and set of conditions. If person A actually has access to 3 litres and person B has access to 30 litres, then B is indeed ‘richer’ than A, by this specific measure. That is variance. However, if both have ‘enough’ for their requirements, then what does it matter that B is richer, when measured in absolute terms? There is difference, or variance, but no real significance in this specific instance. As long as both have ‘enough’, then the very real (tenfold) difference lacks any real significance for us, in this admittedly limited example.

So then, with relative poverty, we hit upon the concept of THRESHOLDS, however defined, which somehow guide us as to what is ‘enough’ for our needs. This might be thought of as an upper limit threshold, with any more being effectively surplus to our immediate requirements. With respect to the 7 Layer Poverty Model, however, our focus will often be drawn more to the lower threshold. That is, how much is ‘not enough’? The upper limit threshold may remain of some academic interest; the lower limit threshold can often become a matter of life and death for the person in question. Quite significant then.

HOW MUCH IS NOT ENOUGH? For each of the Poverty Model’s 7 layers, there is the working notion of a lower threshold, relevant to the individual (or group) concerned, below which humanitarian concern would not reasonably wish the individual to go. The World Health Organisation, among others, is behind large quantities of useful public information on what the human body typically requires, at various stages of development and for varying degrees of overall wellbeing.

This can be translated into assumed global standards and recommendations, regarding the Humanitarian Basics of water (drinking water quality standards) and food (recommended daily amounts). In the absence of some better alternative, we would encourage the adoption of the relevant WHO’s guidelines in such matters, as to what constitutes such things as ‘drinkable water’ and ‘adequate nutrition’. But what of clothing, shelter, healthcare and the rest of our 7 Layers? WHAT ARE MINIMUM HUMANITARIAN STANDARDS? In short, we believe these are best generically outlined, but locally defined. We do not believe it is practical to define a single global standard for shelter, for example. Consider the relative requirements of Eskimo igloos, versus Bedouin tents, versus those groups who spend their entire lives on the open water in parts of Asia. Each requirement is shaped by the chosen lifestyles of the people group concerned. We believe that the best people to ask would be the local people themselves, testing what they say against comparable experiences and practices elsewhere. We will illustrate with the example of clothing, but first we must unpack the 3 elements that most interest us, within each Humanitarian Basic layer.

WHY CONSIDER ATTRIBUTES, ACCESS & AVAILABILITY? For each Humanitarian Basic layer of the Poverty Model, there are 3 things to consider: Attributes; Access; and Availability. The first considers upper & lower recommended thresholds for the key things we might want to measure. Imagine a notional range from 0% to 100% for each factor. Once the upper threshold is reached, there is no particular relevance for us to continue measuring the attribute beyond that 100% threshold figure. An assessment below the minimum threshold effectively counts as ‘none‘, while an assessment above the ‘good enough’ level would score as ‘high‘. The second factor within a layer, assesses the realistic, real-life choices from the perspective of the individual and considers how accessible the best Humanitarian Basic of a given ‘quality’ is, for the individual concerned.

Here we must consider ‘Most Probable Choice’ (MPC) for that individual. If a person must make a daily choice between obtaining good quality water located an hour’s walk away and poorer quality water nearby, our measure must be based on the MPC of that individual, regardless of the choice that we think WE might, or they should make, in their circumstances. Access is again best assessed, for our purposes, with a ‘Simple‘ high/medium/low/none system, or a more ‘Detailed‘ 0-9 assessment system if and when required. Other posts on this site cover the assessment of ‘Access’ in more detail. To get an idea of how Access is measured comparatively, try taking our Global Poverty Survey to experience the questions yourself, easily accessible from this site’s home page.

Once attributes and access (based on MPC) are determined for the individual, then we can consider the Availability of that ‘supply’ to the individual. We must recognise that those facing relative poverty typically face fewer & starker choices, when it comes to disruptions to their lives and livelihoods. This is experienced by them as variations in availability of any given supply, through more frequent and significant disruptions to the ‘normal’ supply of a given Humanitarian Basic. This sounds more complicated than it is.

Consider a person who is used to the supply of a reliable source of good quality fresh water, from a well in their garden. That well represents their MPC for water. In that sense, they have free, unrestricted access to a regular supply of good quality drinking water, but we would assess their ‘access’ at 2, rather than 3, because it is not immediate and ‘on-tap’ within the dwelling. However, during a dry season, or under extreme drought conditions, the water table feeding the well may fall and the well could run dry. In that case, availability of supply is disrupted and we must consider the MPC of alternative sources of supply for that individual, in which case their ‘access’ measure would change accordingly. The implications of the MPC in such cases may be minor, or major. They may even be life-threatening.

Having grasped something of the attributes, access and availability considerations for water, let us now apply the same approach to something far less generic and less consistent between individuals worldwide: Clothing.

ATTRIBUTES OF CLOTHING: THE 5 C’S Clothing, like all the other Humanitarian Basics, is of interest to us from the perspective of the 3 A’s: attributes; access; and availability. That sounds nice and consistent for our core model, but what does it translate to on the ground? How can you legislate over what count as minimum thresholds for clothing, such that you can determine who suffers from ‘clothing poverty’ – even assuming there is such a thing? (For those who doubt the use of such a term, be aware that the term ‘fuel poverty’ is well-used in political and media circles in the UK. It is currently defined there, as households spending more than 10% of their take-home income on fuel.)

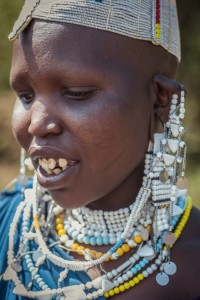

We propose 5 C’s as the most relevant attributes to consider for Clothing, but the notion of ‘Clothing’ should be broad enough to include such related subjects as make-up, hair, decoration and other adornments. We suggest these as global, generic model guidelines, that are then best used to assist determining what is locally and culturally relevant to the people groups being assessed.

In the absence of some compelling reason to adopt alternative guidance in a specific case, we suggest the following: 1. COVERING: There is typically a perceived role for clothing, that it should be sufficient to provide adequate, culturally-relevant covering. This pertains to both protection from the elements and appearance. It deals with both the experience of the wearer and the impact on the observer. 2. COMFORT: It is recognised that when it comes to clothing, compromises between attributes are often made. Common sense and our own experience show that the wearer may choose to sacrifice some comfort in the pursuit of some wider goals. However, the generally accepted principle here is, all other things being equal, adequate clothing should be comfortable for the conditions typically faced. Those conditions may be Sub-Saharan or Arctic. Again, the primary consideration is the most probable choice (MPC) for that individual. If the person chooses uncomfortable clothing for the sake of some other goal, that is one thing. If they have to wear uncomfortable clothing, because they have no other reasonable choice – that is another. Comfort encompasses all relevant considerations, including warmth and fit, combined with weather and waterproofing for typical year-round conditions.

3. CONVENTION: This attribute relates to what is considered socially normal, or acceptable for the people groups to which the individual belongs. This might include work, religious and other relevant social scenarios. Hence, one might be considered ‘poor’ if one does not have the range of clothing considered appropriate for the typical range of social functions for the individual, whether ceremonial or otherwise. It may defy local social conventions to show up at a religious ceremony in work clothes. The author remembers wearing a traditional Bangladeshi ‘lungi’ to a formal ceremony, not realising that it was considered casual work wear for rural men. Even the ‘poorer’ locals advised me that it was not considered appropriate for the occasion. I was ‘richer’ than the local people, but I was still ‘poorly dressed’ – and to them, that mattered. Again, the need for local people to help define relevant thresholds for the attributes is clearly evident.

4. CONDITION: Clothing is subject to ‘wear and tear’. At the same time, latest fashions may even sometimes favour a ‘distressed’ look, costing hundreds of dollars to achieve. While we all accept that we cannot wear all new clothing all the time, there is also a lower threshold where the clothing being worn goes below a minimum socially-acceptable state. Again, our particular interest is where the person concerned wears such clothing as their MPC, not out of positive choice, but rather driven by necessity. 5. CHANGE: The principle here applies before wear and tear. It relates to prevailing social norms about the individual possessing and wearing a periodic change of clothes. While members of religious orders may choose a life of relative poverty and wear pretty much the same style of clothing each day, even here there may be an expectation regarding the frequency with which their clothes are washed. This will usually dictate a suitable change of clothes.

Thus, taking all 5 attribute considerations together, one might reasonably look for a locally-defined minimum ‘wardrobe‘ of clothing; a collection of basic items (adapted for size, age and sex, religion, customs, etc) that might still mark the individual out as relatively ‘poor’, yet adequately sartorially equipped for participation in their community. It is against THAT locally-defined and culturally-relevant standard that we then assess an individual’s position.

Using the Simple Assessment approach to the Model, would deliver a score of high, medium, low, or none against each of the measurement criteria. Note that to score ‘none‘ does not require that the individual has NO clothing at all, but that their position is locally accepted to have gone below the minimum acceptable threshold for any individual in that culture. WHY MEASURE THIS STUFF? Let us keep in mind why any of this matters. We are recognising that poverty is a relative term, a concept consisting of 7 key layers in our Model. Having defined poverty generally this way, we want to move towards mapping it accurately, person-by-person, for anybody on the planet. This enables us to better consider the ‘Poverty Profile’ of the individual. This is not to label them negatively with another ‘buzz phrase’, but to give all stakeholders a consistent view of the present state of that individual, seen through that individual’s own experiences relative to their culture and community. (Follow this link for more detail on Poverty Profiling).

All this is not just theory. We’ve actually done it, just to prove it is possible. Via the picture link on the Home page of this site, you can take our ‘Global Poverty Survey’, which has been constructed as an online Simple Assessment survey, using the Standard set of questions. At the end, we ask people to enter their Country & nearest City or Town. This way, their details remain confidential in our example global Study. However, responses COULD be linked to exact GPS co-ordinates, if the Study required it. Alternatively, it is possible to copy and paste in a URL web address to the relevant location, using Google Maps referencing, as a record of a more precise location. Already, we are capturing responses from countries like Afghanistan, Sierra Leone and Kenya, as well as from more developed nations, like the UK. So go ahead & try it yourself. Make yourself that one in a billion.

Simple or Detailed Assessment approaches assist us greatly when we come on to “Map Poverty”, for a given individual/group and time period. I might consider myself among the top “1% of the 1%” most privileged people in the world; but I can still have my status assessed to generate a Poverty Profile, using the 7 Layer Poverty Model – just like everybody else. All I have to do is answer some experience-based questions and choose which statements best describe my own situation. In our example Survey, you do the compound calculations yourself, based on your own responses. However, a full online system would complete all such calculations automatically and tie them to a unique GPS location, as required. Imagine what access to that quality of data might do to assist current global efforts to prioritise resources in the eradication of poverty.

This is part of the power of the Poverty Model. It can be usefully applied to every one of the 7+ billion people on the planet, while in no way claiming to be exclusive, or exhaustive. Our own agenda concentrates most on those considered among the poorest of those billions. However, the Poverty Model shows no such bias. It applies equally to all. That is why we want you to understand it, use it & explain it to others who will listen. And we thank you again for being… One in a Billion!