By measuring and maximising their ‘input’ impact. Catchy, right? Let us now explain that giant mental leap for you…in “15 Smaller Steps”. Our joint goal here is to help solve poverty sooner, not necessarily by “Spending more”, but by “Spending more wisely“. Once donors are convinced their dollars are being spent effectively, we believe they will be ready to spend more – IF that is what is clearly required. But how do we achieve that greater effectiveness? The 7 Layer Poverty Model recognises 7 key ‘fixers’, or stakeholders, in overcoming poverty for any affected individual on the planet. These are: the individual themselves, their household, their community, in-country governments, social entrepreneurs, multilateral agencies and NGO’s.

Each of these fixers works individually and collectively, with varying degrees of success, in overcoming poverty for the relevant individual. Our 3 step plan to overcome more poverty sooner, is to define poverty, map poverty and focus these fixers. The first two steps are covered in more detail elsewhere on this web site. With the third step, we see one of the most vital tasks with fixers is to get them spending their collective resources more effectively. This is particularly so for decision-making at the MACRO organisation level, but is also true at the MICRO level, in the individual’s own life and household. We have provided additional tools under our overall ‘focus fixers’ heading, to make the fixers’ collective task a little easier. In addition to those tools, here are 15 considerations for all, to make for a smoother journey towards smarter spending:

Since 1945, an estimated US$1 trillion has been invested in overseas aid, apparently. Someone has been counting. Above and beyond that, each year, governments, multilateral organisations, NGOs, faith groups and social entrepreneurs together spend hundreds of billions of dollars more in crisis relief, aid, development projects, health programmes and other initiatives aimed at overcoming various aspects of poverty. Given all that existing spend, for now our primary suggestion is NOT that more should be spent, but that what is ALREADY being spent could be invested more effectively. Much more. And better tools for the workers is a key part of that. That’s where we come in.

In process thinking, these hundreds of billions of dollars being spent each year count as OUTPUTS from one set of processes and INPUTS into another. Simply put, all this money is the net financial ‘Output’ of all the different activities designed to raise donor dollars from governments, multilateral agencies, NGOs, companies and individuals. That money has typically been raised for specific reasons and it usually comes with certain ‘strings’ attached, as to how it is to be spent, when and on what. With those strings attached, all that money becomes an ‘Input’ into the overall global financial system and poverty reduction ‘machine’ and various people have to make decisions about how best to allocate those resources. The trouble is, it can operate less like a well-oiled machine and more like a disparate set of standalone gadgets, each with varying degrees of functionality and effectiveness.

Imagine, for a moment, a massive game involving two sides, a match between two major opponents. One team, which we’ll call Team P, is powerful, well-co-ordinated and formidable. The other team, which we’ll call Team S, is not actually a single team at all. It is a collection of members of other teams, who do not always act as if they are on the same side. They often don’t communicate, speak different languages, come with all kinds of different equipment and even play by different RULES! They don’t even answer to a single coach. They all just rush at the other team as they each see fit, following their own particular sets of rules and strategies. How do you think such a match would go in the long run?

Team P is poverty. Its ‘strategies’ are well proven, well co-ordinated and complementary. Consider the mutually reinforcing effects on global poverty of disease, illiteracy, war, floods, famine, corruption and oppression. If they are NOT deliberately co-ordinating their efforts, they sure do seem to ACT like it sometimes. Now consider Team S, the ‘Solutions’ team. Lots of different players (stakeholders, agents, actors). Governments, NGOs, multilateral agencies and individuals – all coming to the match with different game plans, strategies, tactics and rules. It is hard to operate most effectively as a team, when you cannot agree on a common game plan, or set of priorities. Yet all the players would generally agree that they face a common opponent, in poverty itself. Find out more on establishing a common set of ‘fixer’ priorities, here.

We believe that the 7 Layer Poverty Model provides ALL interested players with a commonly-shared and commonly-understood Model, focusing minds on what they are all there to do and how they collectively plan to do it. It also provides a mechanism for measuring progress towards that common goal of overcoming more poverty sooner. The Assessment tools we propose can help provide the feedback needed to assess the IMPACT that ‘players’ are individually and collectively having in the ‘game’. It’s a serious game with serious consequences – and we want the players themselves to get seriously organised. We recognise 7 key players, all represented simply in the single Model image below.

It is recognised that when organisations and individuals spend the kind of ‘Input’ sums we are talking about here, they may well have multiple different motivations in mind. There is continuing debate as to how much certain countries, like the USA, tie their aid spending to specific trade-based agreements, which in turn tend to benefit America as the donor country. Whatever the TRUE motivations to such measurable inputs, there is general recognition that at least SOME of the motivation is to help overcome poverty in its various forms and to facilitate development.

(The above picture is of ‘sad money guy’ – you’ll see him appear a few times in this article, when certain challenging money issues are raised…)

While MONEY may be the most evident and easily measurable ‘fixer’ RESOURCE input, there are also other significant inputs, or things which can be ‘spent’. These include donor time, energies, attention and other resources (‘TEARs’ for short). Some of these are not so easy to measure and track, but we still know they take place, nevertheless.

If we logically count money within the broader category of ‘Resources’, then we can summarise all the above, by saying that our various fixers and other organisations throughout recent history, have INPUT a lot of TEARs into the world system to help overcome poverty, whatever the varying purity of their motives for doing so. Together, these INPUTs achieved certain OUTPUTS, which in turn have been variously measured and tracked (or not), to their respective ultimate IMPACTS.

In accounting terms, it is usual for an organisation like the UN or a national Government, to track grant monies coming IN and then what those grant monies are being spent ON. Assuming they have nothing to hide in such transactions and to help minimise the risks of waste and corruption, they can make the details of such transactions public and open to external inspection. This is generally referred to as ‘TRANSPARENCY’. We heartily advocate transparency from all participants in such processes, at both the input and output levels. It is recognised that, by comparison, time, efforts and attention are relatively hard to track – but money and assets should NOT be. A simple principle should be that those individuals involved in the end-to-end process, should take as much interest in openness and transparency as they would if it was their own money being spent.

Once we have transparency on both Inputs and Outputs, we can then start to assess whether those generating the Inputs are happy that the Outputs correlate to those Inputs and whether they match any expectations set. For example, if the USA gives US$1 billion to a Global Fund to tackle Tuberculosis, Aids and Malaria, it should be able to track whether that money was actually SPENT on approved programmes to do just that. Agreed? Some of that Input money will have to be spent on administration, as somebody has to track the money, report on it and actually manage the programmes themselves and the multiple organisations running them. This is sensible SUPERVISION. Money does not manage itself; somebody needs to do it and they usually need paying to do it – in the form of a salary, not a bribe. Hence, it is usual for some of the Input money to be spent on actually managing the money and how it is spent, as an Output.

Outputs are still NOT the end of our ‘end-to-end’ story. Far from it. Think of our example of a Global Fund to tackle Aids, Malaria & Tuberculosis. One actually exists. It’s a BIG one. Recently, it was quoted as being some US$20 billion in total. That’s a lot of ‘Input’ to track. It has not all been spent, but some of it has been. This will have been spent on certain selected ‘Outputs’. Among those many outputs might well be treated mosquito nets, designed to kill or deter the malaria-carrying mosquitos from biting and infecting people as they sleep, in a given target country. This Output is aimed at prevention rather than cure.

Somebody had to assess all the various prevention options and weigh up their relative cost-benefits against alternative cures. Then once the mosquito net idea was approved, a further selection BETWEEN various nets on the market had to be made to pick the ‘winners’. They then needed to be purchased and distributed. Various people and suppliers then needed to manage the international logistics of all that.

If you were to examine the whole operation at this point, you would observe (transparently) that lots of money will have been spent as Outputs. Yet not a single mosquito net has so far reached a person in a high-risk mosquito-infected area. Big inputs; big outputs; plenty of administration; zero impact so far. Get the idea?

Now we come on to consider the OUTCOMES. If a million mosquito nets are properly distributed to those assessed as needing them, then that would count as an ‘outcome’, in process thinking. One million people now have mosquito nets that may not have had them previously. Such outcomes can be measured with moderate success. You can track that the chosen transport organisation was given them and that the chosen distribution network representatives handled them along the way, but you may not always know the names and locations of all the individuals who ACTUALLY received them – nor whether they were actually the ones assessed as being most in need of those nets.

If you have an individual holding a thousand nets for distribution, each worth US$10 on the open market, you have a dual challenge. On the one hand, US$10k is a lot of asset value to leave in one local person’s power to distribute correctly and fairly, without any kind of supervision. On the other hand, if you pay a separate person, or organisation, to supervise such distribution, there is an INCREASE in administration costs – perhaps as much as US$1 per net. This all counts as spend against the Output figure – and all before any person receives the actual net itself.

So let’s say you have agreed to pay the extra money , to ensure you have a properly-supervised ‘outcome’. 1 million people now HAVE mosquito nets. You may even have paid EXTRA again to be sure that the nets reached those who are most in need and the intended, priority recipients from the outset. Happier? Good. Now, how do you make sure that recipients USE them properly? You need some kind of education program. You cannot just distribute a million nets and expect them all to be used 100% correctly 100% of the time. So that means spending more Input money on the Output of education and message reinforcement.

Are you getting the hang of this end-to-end picture? This might include what to do if and when the net is damaged. Of the 1 million nets distributed, let’s say 90% reach their originally intended recipients, thanks to our excellent supervision mechanism. Of that reduced number, 80% of those recipients use them correctly, 100% of the time, with no errors, abuses, losses, lapses etc.

How would we KNOW that these figures were correct? Yes, you’ve guessed it! You would have to spend more ‘output’ money to conduct field surveys to check. This means additional spend with no additional nets being distributed. However, it may be considered money well-spent for various reasons. It might help increase overall correct usage in the long run.

At this point, you would have your reliable Outcome figures. Lets just say the net (!) figure was 66% (two-thirds) overall correct and consistent utilisation. Remember that people only need to be bitten once by a single mosquito to be infected, but would need to protect themselves 100% correctly and effectively every day to be sure to avoid that single occasion. This leads us on to measure IMPACT. Impact is the whole reason we have been doing all this, all the way back to raising those donor dollars in the first place, if you can remember that far back.

The way to do that would be to select an appropriate thing to measure. These are often called KPI’s, or “key performance indicators“. They are an approximation to measuring actual impact, in the absence of an exact impact assessment measure. In this case, we might want to track RATES of NEW malarial infection, for those using the nets, compared to those not using the nets, or against previous rates of infection BEFORE the nets were distributed.

There may be multiple factors influencing overall local rates of malarial infection, even assuming that data is being reliably recorded in the target impact communities. For example, the mosquito net distribution may not have been an ISOLATED program. There may well be a parallel program spraying the mosquito breeding areas with insecticide, to reduce mosquito population numbers. Yet how would we KNOW the separate effect of the nets? Yes, it’s time to get your cash out again. Somebody will have to accurately measure those rates of infection and collect the data. Again, that costs money, but it can be money well-spent, to be sure of just what impact the mosquito nets are having.

Having done all this, you can NOW make a reasonable estimate of how effective the nets are on their OWN, when properly used 100% of the time, undamaged. Clearly, people do not walk around in nets during the daytime, so mosquito bites can still happen. The overall impact then will NOT be eradication by nets alone. That impact would require a combination of prevention and cure programs working in parallel over time. There will also be the consideration of the relative value for money in eradicating the last and most difficult residual 10% of all cases. The cost-per-case reduction may get higher and higher, if that is a program measurement criteria being used. However, the objective of the overall program may indeed be complete eradication, in which case, different economic drivers would influence the long term decision. These are ALL valid considerations that we want the poverty ‘fixers‘ to focus on. Still with us? Then let’s continue…

From this ‘simple’ example of what seems to be a simple initiative and solution, to a specific element of one aspect of poverty reduction, we can see the benefit of understanding the end-to-end process, between well-meaning donor and poverty indicator impact. The end-to-end process typically follows the same sequence we have described above, namely: INPUT-OUTPUT-OUTCOME-IMPACT. Measurement of the first two steps is easier. Measurement of the latter two steps is more challenging and costs money, if it is to be done well. The costs can be minimised by appropriate field sampling techniques, but there will still be some. In this context, there has been increased attention given in recent academic literature to randomised control trials, as a means of more accurately assessing the true distinct impact of various poverty reduction initiatives.

Impact measurement is one area where the 7 Layer Poverty Model can be useful – at minimal cost and with minimal expertise. It helps capture the ‘before’ and ‘after’ scenarios swiftly, simply and effectively. The Simple Assessment does not include a specific question on malaria by default, but a particular Study could easily be adapted to do so, while still fitting within the overall standard Model and Assessment framework. If an organisation is already investing in the resources to measure field impact of a given program on individuals, asking those same individuals an additional list of 21 questions that takes 5 minutes to complete is not an unreasonable expectation, or additional burden.

So how does this all relate back to the original goal of ‘focusing fixers’, in the third step of our global poverty reduction strategy? It does so by concentrating all interested parties’ attentions on the primary reason we are doing this: not to generate inputs and outputs, but to achieve positive impacts and assess just how positive those impacts are. Once we know which inputs ultimately lead to the best long-term impacts, then we can be smarter about what inputs we direct to where, for the greatest intended positive impact. This may also encourage donors themselves to consider greater inputs, as they can direct their own ultimate donor bases to the impact results that are demonstrably being achieved. This becomes a virtuous circle, reinforcing positive action among the team of ‘fixers’.

In summary then, we seek TRANSPARENCY for Inputs and Outputs, combined with MEASUREMENT of Outcomes and Impacts and public ACCOUNTABILITY for the ones making the various decisions throughout the end-to-end process. This approach gives us the best opportunity to maximise overall impact success in the field of poverty reduction, overcoming more poverty sooner with the same resources – through better co-ordination.

Taking an idea from IT Service Management, we recognise that “you cannot manage what you do not measure and you cannot measure what you do not define“. This principle is behind why we insist on a practical definition of poverty that we can actually USE. Others are welcome to their own definitions for their own purposes, but we insist on one that makes it possible for us to measure – and therefore manage poverty. The 7 Humanitarian Basics give us the specific things we want to measure. The next stage is to determine WHAT aspects about each Basic we wish to measure.

We don’t want to measure everything about everything, so we compromise in the interests of pragmatism. We want to measure the things that matter most to people: life, health, comfort, wellbeing. Then we measure the availability and accessibility of those things which matter most. We do this all in an Assessment survey, positioned as a banding of four statements in response to 21 questions. Two different approaches serve different purposes. The Simple Assessment provides the simplest method, where broad distinctions are the most pressing need of the given Study. The Detailed Assessment allows for greater differentiation between bands in the responses, although the ‘Standard’ set of 21 questions can remain the same, assuming no need for adaptation for the given Study’s purposes.

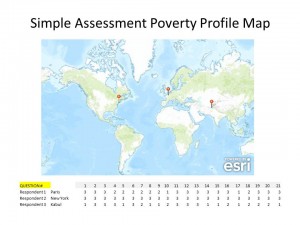

The output of the Study will typically be data in a format that permits drilling down into every individual’s response, but also permits summarising data by geographical area. Hence, any reviewer can gather a useful impression of what the scale and dimensions of poverty are for the studied population of respondents. Such data can help show the present starting position, before new programs and initiatives are implemented, to overcome the various aspects of the poverty being measured.

Taking wisdom from Rudyard Kipling’s 6 Honest Serving Men, the Model and the Assessments provide the who, what, when and where. They do NOT cover the ‘why‘ and the ‘how‘. It is down to the ‘fixers’ reviewing the data, with suitable local knowledge, to understand what factors are causing the poverty observed and how best to overcome them. Whatever ‘how’ is chosen, the Model and a repeated Assessment at some suitable later date will help determine the effectiveness of the given initiatives, in that chosen timeframe. Since the fixers will all be clear on what is going to be measured, it focuses them to concentrate on those activities that will best impact the key measures in the timeframe.

Our advice is that the more public such Studies are made, the easier it will be for others to learn from them: what works and what can be improved upon.

The literature is quite plentiful on aid and development initiatives that don’t go so well, because people DON’T FOLLOW the advice set out above. Here are some examples:

- Corruption: In 2013, Germany suspended its contributions to the US$20 billion ‘Global Fund’ to tackle tuberculosis, AIDS and malaria, due to discoveries of misappropriation accounting, being used by multiple countries who were recipients of its funding.

- ‘Misplaced’ Funds: The experience of some teachers in Honduras was quoted in 2007, by the UK’s ‘Telegraph‘ newspaper, reporting on exposed corruption. A survey followed the money allocated by central government for teachers’ salaries through the Honduras government system, to a sample of schools. It counted exactly how many teachers were actually teaching in the classroom. Because of leakages en route, the employment of phantom teachers, and the non-appearance of real teachers who had other jobs, only 20 per cent of allocated funds ended up paying for teachers in the classroom. However, once each school was notified of the amount due to it, pressure from parents ensured that the position improved. A later study showed that 80 per cent of the money now reached the classroom. Transparency works.

- Wells abandoned, or non-functioning: Adventure Project discovered that on average, in developing countries, 38% of wells were broken, or non-functioning and that they often break down within the first 2 years following installation. Their solution was to train and equip a group of well repairers. Why didn’t the original well boring organisations think to do the same?

- Water filters: In 2012 in rural Kenya, the Flame On charity identified that a separate water charity was distributing filters, but without the proper logistical and training support. As a consequence, the filters were left on the shelves in the rural homes that received them, untouched.

- Large scale projects: The general danger of such large scale projects is that too much money can become concentrated in too few hands and the potential for corruption is thus dramatically multiplied. Once committed to, such large projects may be considered “too big to fail”, forcing donors to continue contributing, even when there is clear feedback that the original benefits predicted, will not be realised. Smaller scale projects spread risk – in a number of ways.

A Master Class in decision-making in a couple of paragraphs? OK, we’ll give it a go! (For a more detailed article on this point, click here). We recognise that any fool can be wise AFTER the fact, but few dare be wise before it. You do not have to look far to find ill-advised aid and development projects. Yet in the same way, you don’t have to look far to find businesses which fail – but you don’t see people giving up on the idea of running businesses worldwide, do you? As Acumen have said: “If failing is not an option, you’ve ruled out success as well”. Our aim is not to ‘demonize’ failure, but to identify what its root causes were. It may be embarrassing for the individuals concerned, but can be rather useful for everyone else.

“If we will not learn from the mistakes of others, we are destined to repeat them ourselves. And if we will not learn from our own mistakes, we are destined to repeat them again and again”. (Give A Billion)

Many will be familiar with the ‘decision square’, mapping importance and urgency respectively on crossed vertical and horizontal axes, each of which ranges from ‘low’ to ‘high’. To form the decision ‘cube’, we have simply added a third dimension: degree of difficulty. The net result, all other things being equal, is that our resources are typically best prioritised to focus on the things which are: most important, most urgent and easiest to deal with. When implemented, this approach gives the rest of the stakeholders an overall, early project ‘boost’, that significant progress is being made – and quickly. Such desirable project outcomes are sometimes called “quick wins“.

It is recognised that when multiple stakeholders meet together with an overall vested interest in the success of a project or program, they may not equally share the SAME sense of importance, urgency and concept of relative ‘ease’. This remains true the world over. The general principle should be that those feeling the greatest sense of priority, should shoulder the burden of explaining to OTHER stakeholders, why that same level of priority should be shared across ALL stakeholders, in the light of the agreed overall aims and priorities of the project.

The cost of resources being invested will also not be equally split. Those experiencing the greatest benefits should seek to find mechanisms, whereby the agencies bearing the greatest costs to deliver them should receive suitable motivation to proceed. Where costs and benefits are mismatched, this is a risk to the overall project success – not to mention team morale. For example, if the bulk of the costs are with stakeholder A, but the bulk of the publicity and recognition goes to stakeholder B, then stakeholder B should actively look for ways of helping A with contributions to their costs, or increasing the publicity and recognition attributed to them. Otherwise, inevitable internal project tensions will arise.

When considering stakeholders in the 7 Layer Poverty Model, the individual facing poverty remains ever at its heart. The challenge is to place the most suitable tools in the hands of that individual, as the most motivated to overcome their own poverty. Simply put, if there was some handle that such a person could ‘crank’, to lift themselves out of poverty with absolute certainty, then we would expect to see them cranking that handle with all the energy they can muster.

So the question arises: what sort of tools would work best and what activities can that individual best engage in, to help lift themselves out of poverty? Underlying answers to this question, is the common issue of PERSONAL PRODUCTIVITY. How do we help each individual facing poverty become MORE PRODUCTIVE? There is the traditional saying: “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime”. This saying is really just drawing our attention to personal productivity as a vital tool in overcoming poverty. Bear in mind that in practice, we will be thinking far more widely than just the idea of fishing, but effective engagement in ‘productive behaviour’ still remains vital. Also bear in mind that there is a trade off between short and long terms objectives here.

Imagine if it took a person 3 years to learn to fish, then until that time, there would need to be some way of funding them until they began fishing for themselves. This is the principle of funding training, or education. Many will agree that a good quality education is vital to helping individuals around the world overcome poverty. But education costs money and while a person is being educated, they are not free to be earning money at the same time. If a good quality education lasts 15 years, then for 15 years, somebody somewhere needs to fund that individual until such a time as they can USE that education to become ‘productive’.

In practice, many will take on a part-time job in parallel with their education, to help fund it. Children requiring long term education are perhaps the most extreme example of having to make the trade off between short term productivity and long term benefit. Overall, most will agree that a good education for 15 years will equip a person better for a lifetime of being more productive. However, who is best-placed to afford to fund that person? Our view is wealthy donors in more developed nations. However, ANYTHING other stakeholders can do to further facilitate and encourage such long-term investments would also be VERY helpful. Any ideas?

In the meantime, there are others for whom education is not the immediate answer and the challenge of increasing their productivity is a more pressing and immediate one. In the absence of adequate PERSONAL productivity, someone else will need to fund a person’s daily living costs – and GO ON funding them indefinitely. This is not the most useful goal to focus limited resources on.

It is not simply a matter of giving them all money, as there is the issue of price inflation. In economics terms, inflation is the typical consequence of too much money chasing too few goods. To help illustrate the point, we must imagine an extreme and rather unlikely scenario. Imagine an island of 100 poor people facing varying degrees of poverty. On average, that island economy produces just enough food to feed the 100 people. The daily food portion for each individual is therefore priced at an average of 1 unit. However, as personal productivity is not equal, some of those 100 people generate an income of 3 units per day, while others produce an income of less than half a unit per day.

Clearly then, the poorer island inhabitants are NOT generating enough to live on and will eventually starve, after they have exhausted all their savings, possessions and the charity of the wealthier islanders. Now imagine a rich person visiting the island is horrified by what she discovers and decides to give the poorest people more money. In fact, she gives them so much money that there is now the equivalent of 300 units of income available on the island each day.

However, all that wealth is still only chasing 100 units of actual food production, because the increased income from the wealthy woman was not accompanied with ANY increase in food productivity. What do you think will happen, with all that money now chasing only enough food for 100 people daily? That’s right, food prices will tend to go up. And they will tend to go up to around 3 money units per unit of food. That is inflation.

In reality, few economies are THAT isolated and an increase in demand for food in one area (accompanied by money) will lead to an increase in supply from outside that area, to help normalise food prices, through market forces of supply and demand. However, inflationary pressures will be felt typically, where an increase in money occurs without accompanying increase in local productivity and the associated local supply of the necessary goods. Hence, while targeted injections of money do help, it works best when that money triggers an associated increase in productivity.

In terms of overcoming poverty, there are all kinds of areas within the 7 Humanitarian Basic layers, where efforts to increase productivity could be usefully invested. In particular, increased productivity associated with improved water quality, hygiene, food production, shelter, healthcare and job creation. All these are worthwhile in dealing with our agreed indicators of poverty, across the 7 Layer Poverty Model. If an individual facing poverty is doing nothing else, they could be usefully engaged in such productive activities as: digging wells, maintaining waterways, irrigating crops, intensive micro-farming, building better homes, preventive medical initiatives, and so on. If they don’t have the skills but are capable of learning them, then training would be the relevant first step.

The worst thing to do would be to leave a person idle. In general, they do not want a ‘hand-out’, they want a ‘hand-up’. Some will see various micro-finance initiatives as part of the overall solution, for certain people in this position. Under such schemes, they may be able to borrow the money, to buy the necessary equipment and training, to then make themselves more productive in the local community and economy. That increased productivity can translate into increased income, which they can then use to pay back the initial loan. This has historically been at the heart of micro-loans, even if many have sometimes abused the system, to use the money for mere consumer purchases, instead of productive investments.

The answer to ABUSE in such situations, is not DISUSE, but RIGHT USE. The risks of abuse can be mitigated with the proper controls and well-run systems. Lenders can build up confidence in borrowers, through a sequence of smaller scale loans, before any more significant loans. It will also work better where the loans happen in the context of local community awareness, so that neighbours are aware of what any loan is MEANT to be for. We believe that in most cases, people ‘just want to paddle their own canoe’.

Whatever the types of initiatives considered, they must fundamentally address the issue of personal productivity in the long term. The alternatives are inflationary pressures, or investments wasted on mere consumption, requiring repeated money inputs just to keep the individuals ‘fed and watered’. Such models are not the sustainable approaches that promise to accomplish so much more, for so many more, with far fewer resources.

When it comes to ‘focusing fixers’, we understand that different organisations are seeking to achieve different things and hence they measure different things. However, the drawback to this approach will be that nobody maintains a consolidated VIEW of poverty – other than the individuals in the predicament themselves. Ideally, we would have a unique way of identifying every one of the 7+ billion people in the world and maintaining a Simple Poverty Profile for them all, at the very least. This will remain most important of all, for those facing the worst poverty of all – the billions at the so-called ‘base of the pyramid’.

Since the vast majority of the world’s 7 billion+ people are organised into countries, it makes sense for the national Governments of those countries to obtain and maintain that data, as each individual is a citizen for whom they are responsible. In practice, unless a thought-leader like Google creates the necessary Geographic Information System for everyone to upload their own data into, this is unlikely to happen in the short term.

However, that is not to stop partial and useful progress being made before that time. If the national Government of a country will not do it, then perhaps a regional Government organisation will. And if a regional Government won’t, then maybe a district Government organisation will. Or if they won’t, perhaps a local organisation will. That local organisation could be a charity, NGO, faith group – or just an organised and determined community, who want to make every effort to improve their lives. We have provided separate spreadsheet templates to help with the co-ordination challenges involved, for both the MACRO and MICRO scale levels .

In capturing relevant data, the Simple Assessment statements are, understandably, more oriented towards identifying those facing extreme poverty. Hence, if you conducted a Study in the wealthiest areas of London, Hong Kong or New York, there would be less incremental value in the output of such a Study. Almost all the responses will predictably be in the highest possible bands. However, conducting such Studies among the communities where there is evident and extreme poverty will begin to highlight the extent of the plight of that specific group of people.

The relevant authorities reviewing the data will have more than mere anecdotal data regarding their citizens’ conditions. Such Studies might helpfully be backed with full GPS or other location data, photographs and even videos, as documentary evidence backing up the Study. Such approaches are increasingly feasible for determined individuals to do, with something as simple as a Smartphone with internet access. People just need to get themselves organised.

We encourage that – and we aim to equip such people with helpful tools to get the job done. In future, we would like to facilitate the collection of all such studies into a global common GIS, so everyone could review the findings independently and cross compare them. This may take some years, but we believe it will be worth it. Until then, individuals can capture and publish their own Study data, requiring no more than a simple spreadsheet. These are tools we can all agree to work with, until we can all obtain better ones.

Consider the single issue ‘actors’ against poverty, such as the World Food Programme, Amnesty International, or Water Aid. Their advantage is that by concentrating on a single issue, they can get good at it. The challenge of setting up in a new country is not so big for them, as they know exactly what they need to succeed. However, they only have latitude to move against one indicator of poverty. When they understand that their own donors will increasingly be looking at all 7 of them, they will be more inclined to work with other actors who are tackling other aspects of poverty – whilst still sticking to their own chosen specialism. Indeed, some already do precisely that. After all, it is clear that poverty is a multi-faceted beast and we would do well to maintain a multi-pronged approach in seeking to overcome it.

This is an area where ‘the power of the people will prove greater than the people in power’, as U2 rock-star and self-proclaimed ‘factivist’ Bono says. By producing your own Studies, you create a pool of useful data and help establish the global standard yourselves, without having to wait for the world of ‘experts’ and politicians to decide for you – or worse still, decide it is too hard to sort out at all.

So YOU show them you mean to press on and succeed. Simply make it happen yourself. Become ‘factivists and maptivists‘ like us. Use any suitable opportunity to conduct such Studies, publish the findings and promote the Model – until some better tool presents itself. This tool has cost you nothing to acquire. If you need to adapt it, feel free to do just that. The wheels we all use today have diversified a great deal from the original invention! The internet has prospered by everyone adhering to a set of common core standards, but adapting the USE to their own specific APPLICATIONS. Feel free to do the same yourself, with the 7 Layer Poverty Model, the Simple Assessment and the Detailed Assessment methods, together with the macro and micro level decision-making spreadsheet tools. They are ALL YOURS to use wisely, effectively and appropriately. Enjoy!

As ever, if anyone has better ideas for solving poverty, we’d all love to hear them.

And thanks to you, once again, for being…

One in a Billion!