CLOSENESS-DRIVES-MOTIVATION-DRIVES-ACTION

We want to introduce the notion of ‘closeness’ in driving action towards solving poverty. We use it deliberately, as a term that most people can relate to and feel they understand, without requiring a dictionary definition of the term. Closeness is a ‘feeling-based’ summary of one’s overall attitude towards another. People use it in their most valued relationships, to describe how they feel towards each other, in a common language: “I feel so close to you right now”. The same common idea is used to describe matters when things are not going so well: “You seem so distant”. Although technically speaking, ‘closeness’ is meant to be a measure of physical proximity, we habitually use it to give a sense of how ‘unified with’, or ‘separated from’ another individual we think we are. It is a simple way of describing and summarising the complex way we may actually feel. We believe that the relative presence or absence of this feeling of closeness, materially affects how we collectively respond to the needs of the poorest billion people on the planet.

Clearly, as human beings, we are used to our behaviour being driven by how we feel. If we are tired, we might sleep. If we’re hungry, we might eat. If we’re concerned over a given situation, we might act. Our simple idea is that people who feel closer to others are more likely to be motivated to ACT on their behalf. The closer we feel, the stronger the motivation to act. Agreed? Consider the strength of motivation a mother can have in protecting her child, based on the sense of ‘closeness’ she feels to that other human being. This is not simply a genetic thing. There are biological mothers who admit to feeling little for their own children, in some instances. While elsewhere, a person may feel an immense closeness to a child that is not even their own.

CAN WE MEASURE CLOSENESS?

Whatever the reason, the idea of closeness has come to be used between people, to summarise their overall strength or weakness of feeling towards each other. Degrees of closeness then, though quite possibly hard to actually measure scientifically, certainly seem reasonably easy for people to express. While people may not ADMIT to any sense of absolute measurement of closeness, they can certainly respond more readily to questions of comparison: ‘Which of your friends do you feel closest to?’ We do not know how this concept translates into other languages. We hope that the universal experiences of touch, physical proximity and interpersonal relationships will mean a common language equivalent, via interpretation, throughout the world.

WHAT DOES THIS HAVE TO DO WITH SOLVING POVERTY?

OK, fair point. To recap then, a sense of ‘closeness’ drives motivation and motivation in turn, drives our behaviour. Motivation MOVES you to action. When solving poverty, well-informed, timely, effective, sustainable ACTION is precisely what we want, so anything that leads to that outcome is of keen interest to us. It is this kind of action that we look for among any or all of the 7 key poverty ‘fixers’ recognised in our 7 Layer Poverty Model. It is recognised that MANY other motivations and forms of action may abound in the realm of seeking to overcome global poverty. Our own interest is in how EFFECTIVE a given course of action is and what helps motivate and focus the fixers towards that kind of action. We cannot reasonably ASSESS any such outcomes, without some reasonable approximation to MEASUREMENT. We accept that all attempts at measurement of progress against poverty metrics are, to a degree, “truth-substitutes”. They cannot tell us exactly what the situation is, but we accept the compromise in getting us the closest thing to the truth we can reasonably expect to obtain, under the circumstances and within given constraints.

WHAT FACTORS AFFECT CLOSENESS?

‘Focusing fixers’ is the third of our proposed 3 steps to solve global poverty. When focusing fixers, we aim to use measurement in assessing action impacts and the notion of ‘closeness’ as a key variable when assessing various ‘fixer’ motivation levels. So the loaded question arises: “What are the key factors which then drive a sense of closeness between people?” We can think of a few categories of things. Chief contenders among these seem, to us, to be: emotional, familial, social, ethical, moral, religious, practical, circumstantial, physical, sexual, geographical, political, functional and awareness-driven. That’s quite a list, so allow us to unpack it just a little.

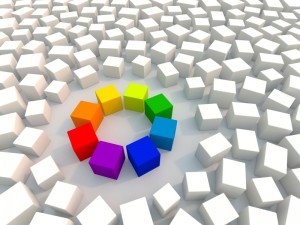

Imagine a circle broken down into many segments, rather like an orange cut in half and viewed from the top. Each of the potential factors in our list is like an individual segment of that circle. The thickness of each segment can give an indication of how relatively important a given factor is in the overall sense of ‘closeness’ between two people, while the bigger the whole circle, the stronger that overall strength of feeling. Got it? With that metaphor fixed firmly in your mind, we will continue. Let’s start with an easier one. Imagine the same mother and baby scenario we referred to earlier. There are reported instances where mothers have been motivated to go to EXTREME lengths in the protection of their children, in some cases lifting off massive weights from their physically trapped children, in order to rescue them from some disaster. By weights, we mean things like cars! That would be a powerful overall strength of feeling represented by a large circle and we would expect the biological relationship to represent a large segment within that whole. Now consider the size of the circle and the thickness of the segments within it, for other types of relationships you have.

CLOSENESS BY DEGREES, NOT ABSOLUTE MEASURES THEN?

If you ask parents around the world if they feel equally ‘close’ to all their children, the answer in many cases, will be ‘no’. It is not necessarily that they feel ‘close’ to some and ‘distant’ from others, but that they experience DIFFERENT DEGREES of closeness. You may have experienced the same thing with your FRIENDS. You feel closer to some than to others. In English, we even have the phrase “close friends”, to distinguish them from others who are – not so close. And there are certain things we would be willing to do for CLOSE friends, that we wouldn’t be willing to do for OTHER friends. This relative distinction becomes important when considering the relative motivations of our 7 key poverty fixers.

Yet not everyone fits neatly into one of those 3 categories: ‘not a friend’; ‘friend’; or ‘close friend’. There are billions of others who we don’t even know yet, including the vast majority of those facing poverty. So just how “close” do we feel to them? It is not even the simplest answer, which would be ‘not at all’ – because in fact we can and do feel DIFFERING DEGREES of closeness, even to people we don’t actually know personally. Have you ever witnessed the devotional behaviour of fans of pop stars and movie icons? Remember, we are not suggesting that such feelings need to be reciprocated by the person you feel close to, just that YOU can sometimes feel surprisingly close to those you don’t even know – whatever the degree.

So, if we can feel different degrees of closeness to people we don’t necessarily know, then what sort of things drive that? We accept the more obvious things like family relationships and friendships, but there’s more. There are also other perceived ties, that bind two people closer. A sense of common religious views can be one. You may have witnessed references to the sense of ‘brotherhood’ between Muslim men worldwide. You might also be aware of Christians who describe themselves as ‘one in Christ’ with others who share the same faith. The differing extent to which those stated beliefs are felt, or actually practiced, is a different matter. The principle is that those of a common faith will often experience a greater sense of ‘closeness’ with those who share the same faith. But the tie of common beliefs and loyalties is not exclusive to religion. We previously mentioned fans of pop stars. Have you heard of teenage girls describing themselves as “Beliebers”, after the surname of their heart-throb, Justin Bieber? Similarly, sports fans will share a sense of closeness to others who support the same team – and a sense of distance from those who support an opposing team. They may even label themselves as ‘fans’ – which is short for ‘fanatics’. And fanaticism itself can become a common bond, increasing a sense of closeness between people.

CLOSENESS AS A UNIVERSAL FEELINGS SUMMARY MEASURE

We don’t debate whether the origin of such senses relates back to former times, when one ‘human tribe’ needed to know if a member of another tribe was ‘in or out’, friend or foe. We simply wish to acknowledge the fact that this sense of ‘closeness’ is common to human beings and is felt to varying degrees and for different reasons. Let’s briefly consider some more of those reasons. Social: if they are part of our community, sub-culture, country membership, language and so on, we feel a greater closeness to them than those that differ – all other things being EQUAL (which they often aren’t). Emotional: plenty to choose from here, ranging from the natural pity humans seem to have for nearly all babies, through to the intense closeness that can be felt for those you most identify with. Political: a greater sense of closeness to those from the same or other countries, who share the same political ideologies. Practical: a greater sense of closeness felt between people facing similar predicaments together. Functional: a greater sense of closeness felt to those who are deemed your ‘responsibility’ in your job, whether fellow staff, or those your job role specifically serves (customers, clients, the cared-for). There are clearly more, but you get the idea.

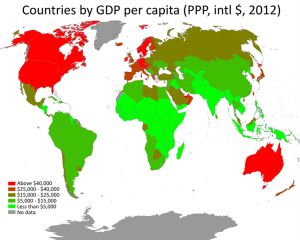

Underlying it all, is the necessary sense of personal AWARENESS of and IDENTIFICATION with the other individual or group. If you are unaware of another person’s existence, then a sense of closeness simply doesn’t register. The greater the level of awareness of another person, the greater opportunity there will be to develop any sense of closeness based on OTHER factors – instead of the ultimate indifference and distance typically felt otherwise. Perhaps this partly drives the idea that: “charity begins at home”. We are naturally more aware of the possible needs of those in our immediate vicinity – in our home, in our community. There is less likelihood that we will have the same level of closeness to those who live in a different country, or on a different continent. Less likely, but not impossible.

Feeling closeness is not primarily driven by physical closeness, but by awareness and identification. Consider friends who met in one country, moved to completely different countries, but remained friends. Physical distance NEED NOT be an issue, but it is certainly one of the key factors to consider. People talk about the idea of the “global village”, where modern transport and the global spread of telecommunications means that people never need feel that far away from each other. You can now talk to someone the other side of the world as if they are standing in the other room.

So what of it? Assuming we now accept that awareness and identification drive closeness and closeness in turn drives motivation to action, what does that mean for solving global poverty?

It means this: That we will be MORE motivated to act on behalf of those we feel CLOSER to. Conversely, we will feel LESS motivated to act on behalf of those we feel more distant from. Campaigns on behalf of poverty charities realise this. If they are to get you to feel closer to the people needing help, they have some obstacles to overcome. Firstly, you don’t know the people involved, so they give you their NAME. The more familiar the kind of name given, the greater the probable sense of closeness. A name turns a ‘some thing’ into a ‘someone’. It is personal. It even works on paper and radio. But we want more closeness – so we give you a picture. When you SEE the person, then what was unfamiliar and unknown starts to become more FAMILIAR – and perhaps closer. If the picture is of the kind that you will respond to more readily (a wide eyed child, for example), so much the better. And a moving, rather than a mere photo image is best of all. It all helps to identify them as human and ‘like us’ in that way. That is why we at Give A Billion seek to use close up pictures of REAL PEOPLE on this site so often. We think it is important to remind all our welcome visitors that we are talking about the lives and livelihoods of real people. Photos help us do that. They help us to feel closer to the person we are seeking to help overcome poverty.

HOW DOES THIS AFFECT THE 7 LAYER POVERTY MODEL?

So then, we recognise the principle that an increased sense of closeness leads to an increased sense of motivation. We also understand that different sets of related FACTORS all add up to give us an overall relative ‘closeness’ measure. The strength of that sense of closeness can VARY over time, so our overall closeness ‘score’ would change with it. We also point out that our goal at Give A Billion is to facilitate a ‘coalition of the willing’, in overcoming more poverty sooner for a billion people. Hence, the greater the genuine sense of closeness we can help foster, between those who want to help and those who could use some help, the better.

So let us return to the 7 Layer Poverty Model once more, to check where this consistent notion of ‘closeness’ helps us and can be incorporated. Remember the person facing poverty stays central to the Model. Of all those feeling ‘close’ to that person, the individual themselves must surely feel closest of all. They are typically the most motivated to overcome their own poverty circumstances. They will remain so, long after others may have given up and gone home. Which brings us onto the next most motivated group typically – the individual’s own household. In most cases, if an individual is facing poverty, it is likely that their whole household may be also be facing certain similar aspects of that same poverty scenario. As the ones ‘closest’ to the individual, it is normal to anticipate that the household of the individual will be the first and next most motivated to ACT to end poverty for that individual, if they can.

If the household is NOT acting that way, then the household is not functioning as one would normally expect a household to function. It is being ‘dysfunctional’ in that sense. If the household is AWARE, has the necessary RESOURCES to act and does not – then the issue is with the dysfunctional household, not identifying closely enough with the individual. Let us call this a ‘Cinderella Syndrome’, after the fairy tale character who suffers neglect and maltreatment at the hands of members of her own household. In the same way, if the household exists as part of a wider Community, that is again AWARE of the poverty circumstances faced by the individual, has the necessary RESOURCES to help the individual overcome those circumstances, and yet does not act – then it is the Community which is now being dysfunctional. This then, is ‘Cinderella Syndrome by proxy’. We are not suggesting that the Community should prop up all individuals for any and every reason, but as we explain elsewhere on this site, there is a recognised minimum standard that we would want all people to exist above, in each of the 7 Layers of the Humanitarian Basics. On that assumption, the “why” reason to act is to be consistent with our own personal standards of being ‘humanitarian’. If we DO NOT act consistent with our declared aim of being humanitarian, then we should not be surprised if we lose that particular label in the minds of others – locally, nationally and internationally. If the immediate Community of a person facing poverty circumstances and trying to overcome them, will not ACT to help that individual, then it should not be surprised if the wider global community asks them to account for such inaction. Is that not reasonable?

Beyond Communities that are either dysfunctional, or lack the necessary resources to assist individuals among themselves facing poverty, then the issue naturally escalates to the relevant Government of the Country (or region) to resolve. Remember that Government is one of the 7 key poverty ‘stakeholders’ in our Model and one of the 4 constituent members of the ‘net’ that underpins the individual, the household and their Community. Perhaps you have heard the saying: “God helps those who help themselves”? Well, certainly Communities can be more inclined to help individuals who help themselves and in turn, Governments can be more inclined to help Communities who help themselves. But they first need to be AWARE of “what” the poverty issues are. That is where the Simple Assessment can help. Rather than giving vague, anecdotal stories of how bad poverty is for certain individuals within certain areas, Government politicians and decision-makers can be better informed and prompted, by more tangible evidence of actual circumstances.

HOW CAN POLITICIANS BEST HELP?

A word of caution on this point. Do not expect too much of politicians. Remember that it is best that they are left to do the things they can do well. Keep in mind the issue of ‘closeness’. If a Community does not feel close enough to an individual who lives within their midst, why would anyone believe that a politician would feel closer and more inclined to act than the relevant Community? In the UK, by way of comparison, there is about one politician for every 10,000 people – and that is in a fairly politician-dense country! What is the ratio in your own country? We ask this, because this site is visited by interested thinkers from over 125 countries around the world, so we are always curious to know. Your own situation could be far worse – maybe even 50,000 people per politician. What can one such politician do to address the many and various needs among 50,000 people, within the constraints of time, budget, mandate, local law and other resources at their disposal? In our opinion, Politicians are best left to help in the best way that they can, through such things as supportive legislation, protection of the vulnerable, humanitarian constitutions, the effective national and local rule of law, freedom from oppression and policies that facilitate individual productivity and innovation. They can also help engage and co-ordinate with the relevant local ‘chapter’ of the ‘coalition of the willing’ stakeholders. When others know the Government is genuinely supportive, it helps increase levels of motivation to act. Solutions often involve the need for local politicians to play their part – and share in the positive impacts of practical success on the ground. Those are things a politician can reasonably spend their time doing. Individual projects and situations are a tougher call. After all, which of the 10-50,000 people in your area do they reasonably focus on? If they have to prioritise, how should they decide which community’s needs come top?

Beyond the national level, we still have the NGOs, the Multilateral Agencies and the Social Entrepreneurs. In terms of closeness, it is variously part of their chosen and defined ‘roles‘ to help overcome poverty. Hence, a degree of empathy is already assumed. For NGO’s, their own reasons for being may limit them to a particular focus, or a particular issue, but they can still play their role within a co-ordinated whole. The larger organisations have the benefits of scale of resources, but greater volumes of need to respond to. The smaller scale social entrepreneurs have the advantage of flexibility and potentially local proximity to the point of need. Most international NGO’s are under pressure to fulfil their expected roles cost-efficiently. They often seek to achieve this through “local partners” in the relevant country. This way, they can show donors that much of the money donated is spent in-country, rather than on central administrative overheads. The local ‘partners’ have the benefits of local expertise, language, knowledge and resources. For these collaborators, ‘closeness’ SHOULD be less of an issue. But it still can be. Local operations can be subject to local prejudices. Preference can be shown in the allocation and distribution of funds and resources, that should have been shared equally among all. The UNHCR Handbook makes this clear in its guidance on fair and equitable treatment of all refugees within its camps.

So what have we learned about closeness and its role in focusing the fixers? The ‘closer’ we feel to someone, the more likely we are to want to ACT on their behalf, when it comes to helping them overcome poverty circumstances. But that motivation is best CHANELLED into fruitful and effective action. Not all actions will prove equally effective. We believe that the 7 layer Poverty Model will inspire better focused action, on more relevant criteria, with more widely engaged resources, to overcome the relative lack of Humanitarian Basics in the lives of a billion people around the world. Closeness gives us a measure to assess ‘fixer’ motivations and potentially why a given Social Structure is not effectively performing its intervening function as expected. Closeness also helps direct our thinking, when it comes to engaging more people in the ‘coalition of the willing’. The ‘closer‘ we can get each willing volunteer to feel to the person they are helping, the more they will be inclined to invest their time, efforts, energies, attention and resources in helping THAT INDIVIDUAL overcome poverty. We encourage a one-to-one sponsorship relationship wherever practical. We encourage households facing poverty to demonstrate their own closeness by their own action on behalf of the individual. We encourage Communities to demonstrate their own actions on behalf of each individual, before they look to outside bodies to help. If someone is richer, they may be better EQUIPPED to help a poorer individual, but they will not have the same degree of motivation of ‘closeness’ that should be manifest among that individual’s own household and Community. If the Community is not already offering such help themselves, then such Communities should not be surprised when they are not offered such help themselves.

There are some supremely wealthy individuals on the planet. Many of those are already major philanthropists. We believe that they will be far more likely to INVEST in projects, where Communities and Countries have already established a solid track record of ACTING EFFECTIVELY themselves. As one commentator put it: they are keen to give ‘hand-ups, not hand-outs’. It is always easier to suggest that someone else should be doing what we are perfectly capable of doing ourselves.

We comment elsewhere on what any Community can reasonably do to demonstrate that it is already seeking to help itself. Such demonstrable action and results will more likely encourage others to lend their additional support. And some of those others may well be billionaires! And if every dollar helps in solving poverty, then a billion should help even more.

So it just remains for us to say, thanks again for being…

One in a Billion!