Poverty is a problem, but whose problem is it to solve poverty? And how exactly can a poverty model help? This article answers both questions. We promote a 3 Step Plan to solve poverty, namely: define it, map it and focus its ‘fixers’. That’s it. All problems, at their heart, are human in origin. Don’t agree? Then take the example of the polar bear. It may be true that some of their natural habitats are under threat, through global warming. However, polar bears themselves do not perceive this as a ‘problem’, as such.

For those that it affects, it is just their immediate reality. For those that it doesn’t affect, they remain blissfully unaware of the issue. In the same way, global poverty is a human problem, not just because it is human in origin, but that ‘problems’ themselves are ultimately all human in nature. Nature itself doesn’t register a formal opinion either way. If it did, it might well consider human poverty as another form of ‘natural selection’; an enforced instance of ‘survival of the fittest’. In contrast to such anthropological Darwinism, human history provides a long track record of human problems being solved by human ideas. Karl Marx (1859) claimed that “Mankind thus inevitably sets itself only such tasks as it is able to solve”. We contend that solving poverty is no different and that the 7 Layer Poverty Model may prove just such an idea. So let’s examine it together and see if you agree.

The challenge to solve poverty is a human one. The 7 Layer Poverty Model is a human idea. It is not the complete answer in itself, but it is a key tool in solving the puzzle, in that it provides a COMMON and consistent way of understanding the complex problem of poverty and its many contributory causes. It is intended to be sophisticated enough so that most experts can use it, but simple enough so that most people can understand it. It draws from simple concepts that are familiar to us all and shows an effective way of combining them in a single, 3-dimensional model, consisting of a 7 layer cone sat on top of a ‘target’. Like this…

It uses a standardised definition of poverty that can be simply understood and simply communicated. That definition can be given in 7 child-friendly words. Poverty is: “not enough of 7 things we need”. To the expert, that translates to “the relative absence of 7 Humanitarian Basics”. But let’s just take the child-friendly definition for a moment.

It breaks down into 3 simple ideas:

1. There are some things we all need as humans

2. There are 7 important ones to keep in mind

3. ‘Poverty’ means not having enough of them.

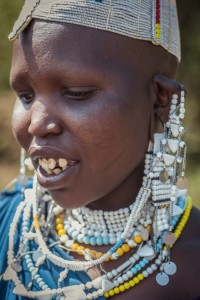

The 7 Humanitarian Basics are: water, food, clothing, shelter, healthcare, engagement (within the community) and freedom from oppression. Could you explain these things to a 5 year old in language they can understand? Could they then explain it to their friends? If so, that is more than half the battle: defining the problem in such a way that most people actually understand it. But is it still powerful enough for experts to use? Let’s now consider the problem from the perspectives of those whose job it is to actually solve poverty – those whom we call ‘the fixers’.

FIXERS: MICRO TO LOCAL LEVEL

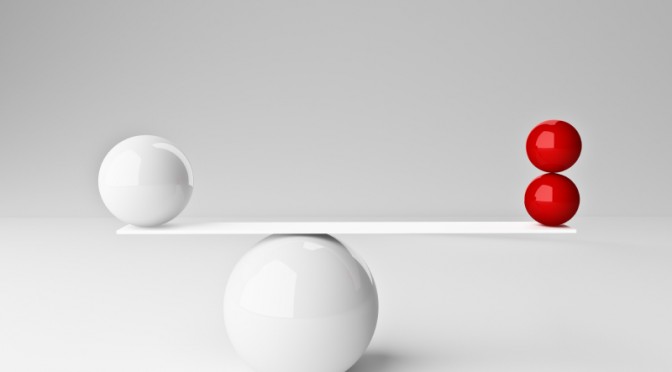

The 7 Layer Poverty Model recognises seven ‘players’, ‘actors’, ‘stakeholders’, or those who otherwise recognise they have a particular role in solving poverty for any given individual on the planet. First and foremost is that individual themselves (excluding those who opt for some form of poverty out of choice and preference). You may have heard the phrase: “God helps those who help themselves” in this context. The Poverty Model recognises that the person typically most motivated to lift any given individual out of poverty, is the individual themselves. The model therefore starts by identifying that motivated individual, represented by the 7-layer cone at its centre – at the ‘bulls-eye’ of a sequence of concentric circles – like an archery target.

With some rare exceptions, people around the world mostly choose to organise their living among others. That model of organisation proves pretty consistent globally. Individuals tend to cluster into households of one or more. Households tend to cluster into communities. Both such ‘social structures’ are thus represented by the two ‘ghost’ cones surrounding the central, individual cone. One can imagine that in many (but not all) cases, the relative absence of Humanitarian Basics experienced by the individual will also be experienced at the household level.

One can also imagine aggregated assessments for Humanitarian Basics taken at the whole Community level, using techniques like the Small Area Estimation approach adopted and promoted by the World Bank. The risk of such aggregated information is the loss of detail for the individual and their household. This is one of the strengths of the 7 Layer Poverty Model, relative to Small Area Estimations, where levels of granularity only extend as far as the community as a whole.

FIXERS: MACRO LEVEL

Within the 7 Layer Poverty Model, the individual, their household and their Community are the first three out of our 7 key ‘fixers’ recognised and represented. The other 4 are represented by the 4 sectors of the target pattern underneath the cone. These fixers are: multilateral agencies, non-governmental organisations, social entrepreneurs and in-country governments. Statistically, countries do not tend to change their boundaries that much, or that often, even though some remain in dispute to this day. This enables us to look consistently at remarkable aspects of the history of poverty globally, at the macro-level, over 200 years and for some 200 countries, using published statistics from the United Nations.

So, surrounding the individual, the Model recognises a household, which may be one or more persons, but is otherwise largely self-defining. They are considered a single ‘household’ because they think and act as such. Beyond that boundary, there is the Community to which the given household is considered to belong, however loose, shifting, or complex those relationships may prove to be in practice. Underpinning Communities is the support (however tangible) of the government of the country to which it is typically considered to belong – such that it would think of that community as its citizens and thus, to some extent, its responsibility.

While countries have long seen themselves as part of various geographic empires, regions and continents, recent decades have also witnessed a particular rise in new multilateral entities, formed through alliances between multiple countries and across continents. Of particular note and influence in the context of solving poverty, are the United Nations, the African Union, the Arab League and the European Union. These are referred to collectively within the Poverty Model (and elsewhere), as examples of ‘multilateral agencies’. They are another of the seven fixers, represented in the Model as one of the 4 ‘sectors’ making up the ‘target’ pattern underneath the cone. We think of it as operating like a ‘safety net’, underneath the individual, their household and their community.

Multilateral agencies have a publicly declared interest in the general wellbeing of citizens who exist beyond the borders of any one constituent member state. The United Nations was formed with the idea that ‘an attack on one was an attack on all’. This reflected a sense of shared problems and shared responsibilities among the member states within the multilateral agency. Member charters and codes of practice define what each member state commits to sign up to. It is typically considered part of the price of ‘membership’.

Such shared public commitments have variously extended to such significant things as: the International Bill of Human Rights; the Geneva Convention; and the Millennium Development Goals. Such internationally recognised standards and commitments are impressive enough in themselves. So many authorities, from so many differing countries, speaking so many different languages, over so many years, have all agreed on them – at least notionally. Those agreements may not go far enough for some member states, but their great power is in their perceived consensus. So it is with the 7 Layer Poverty Model.

Within the Model, non-governmental organisations (NGO’s) may include both charities and religious groups, operating at a local, national or international level. However, this category is usually seen to exclude companies, in the traditional sense. NGO’s may have a tight focus on one particular community, or their reasons for being may extend all the way to international ambitions and activities. The Red Cross, or Red Crescent is a well-known example of the latter. Poverty-focused charities are of obvious interest for us, within the 7 Layer Poverty Model, but clearly most faith group members around the world would also recognise some common responsibility towards ‘the poor’ – even if it may prioritise the poor among the group’s own notional ‘membership’.

The Poverty Model does not expressly exclude companies from having a place within the broad category of NGO’s, insofar as they are usually organisations which are not actually ‘governments’, despite some of them being ‘state-run’ or part state-owned. Companies do have an important role to play in providing employment, which is a factor recognised within the “Engagement” layer of the 7 Layer Poverty Model. Some companies even make notable contributions to charities, financial or otherwise.

However, companies are not treated as a separate priority group within the Model, as their stated goals are not typically seen as primarily distinguishing and serving ‘the poor’ as such, or addressing poverty, specifically. Yes, some of their actions may help alleviate some aspects of poverty, but they would not see it as their primary “job”. Companies have priority obligations to their own stakeholders, as part of their own reasons for being. These may include ‘society’ as a whole, but the majority of companies usually see themselves as geared more towards satisfying shareholders, customers, suppliers, management and staff. ‘Society’ may be ‘in the queue’, but it’s not at the front.

We also think that efforts at persuasion are best directed at the individuals who invest in and run those companies – all of whom may enjoy a greater degree of individual free choice than some of the people their decisions can adversely affect. We recognise that there are many techniques of persuasion in such circumstances and we wholly advocate the positive, constructive ones, recognising such free choice. We do not support the use of intimidation and violence to achieve our goals and in that sense, we do not advocate any perceived need “fight fire with fire”. So how DO we aim to help solve poverty?

We define poverty as the relative lack of 7 Humanitarian Basics. These Basics are organised in a tiered-hierarchy, in recognition that this stepped idea broadly reflects how an individual’s priorities work out in real life for those facing poverty – in its multiple dimensions. Each Humanitarian Basic forms a Layer within the cone structure.

Each Layer can then be subject to a Simple Assessment in terms of 3 considerations: Attributes, Access and Availability – for every individual on the planet and without the need for data aggregation. Such an Assessment is qualified with a measure of high, medium, low or none, based on categorising responses to 21 questions. Conceptually then, every individual can be represented by a 3-dimensional cone, with each of the 7 layers of the cone made up of 3 inter-connecting sectors – all of which can be subject to Simple Assessment. Each individual is represented as being surrounded by their household and Community, in the from of ‘ghost’ cones. The cones together sit on top of a ‘safety net’ made up of 4 sectors, representing the 4 macro-scale fixers.

Together, these constitute the 7 key fixers that we recognise as having a sustainable, long-term interest in solving poverty for every individual facing it on the planet. The collective, shared intention is to assist each motivated individual to improve their own life and circumstances – sustainably. The value of the model is to facilitate a common language and understanding, enabling us to better define poverty, map poverty and focus the fixers sharing the same common agenda. That is how a simple model can help solve poverty. It is a simple, but powerful tool, that can be used alongside Systems Thinking, to overcome more poverty sooner, with the same or less resources.

We hope you will share this agenda with us and with others who will do the same.

And we thank you again for being…

One in a Billion!